THE JOURNAL OF UROLOGY

MUAMMER KENDIRCI, ATES KADIOGLU, UGUR BOYLU AND CENGIZ MIROGLU

Vol. 173, 1879 –1882, June 2005

DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000158162.32214.de

Historical Article

ABSTRACT

Purpose: We examined the urological procedures of the 15th century covered in the surgery textbook, Cerrahiyyetu’l Haniyye.

Materials and Methods: Three copies of the surgery textbook, Cerrahiyyetu’l Haniyye(Sultan’s Surgery), by Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu, who lived in Turkey between 1385 and 1470, were evaluated. The colorfully miniaturized and illustrated textbook, written 536 years ago, covers a number of surgical disciplines, including urology. We evaluated urological sections with regard to the type of procedures, definitions and approaches for certain diseases and surgical tools used for urological operations.

Results: The textbook reviews the surgical treatment of urological conditions such as varicocele, hydrocele, hermaphroditism, imperforated urinary meatus, meatal stenosis, hypospadias, penile and scrotal lesions, and circumcision techniques. It includes definitions of diseases, etiologies and surgical therapies, and describes surgical instruments. The author also illustrated surgical approaches and instruments.

Conclusions: A treasure trove of surgical knowledge, Cerrahiyyetu’l Haniyye has enlightened urologists from the 15th century to the present day.

KEY WORDS: history of medicine, penis, varicocele, hydrocele, circumcision.

In early societies medical therapies were classified into 3 main categories, namely treatment with magic and rituals in societies dominated by religion and religious functionaries, operative procedures using knives in warrior societies and the prescription of medicinal plants and herbs in agricultural social systems. In Anatolia, modern day Turkey, various medicinal practices were used by a number of different civilizations. Surgery as a discipline of medicine had been in practice in this area of the world for centuries.

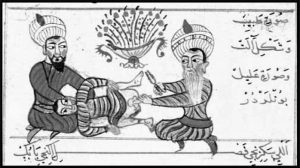

Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu, one of themost influential surgeons of the early Ottoman era (fig. 1), was partly influenced by Ebu-El Kasım El Zehrawi (Albucasis, 936 to 1013), who wrote the textbook, El-Tasrif. In 1468 in the introduction to his surgical textbook, Cerrahiyyetu¨ ’l Haniyye(Sultan’s Surgery), Sabuncuoglu refers to El Zehrawi as a master and mentor.1 His book differed from El-Tasrif in its use of colorful miniatures and illustrations detailing various surgical procedures.

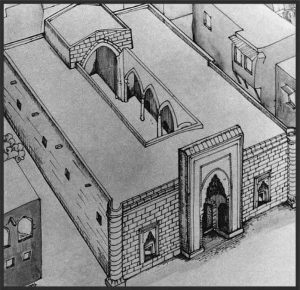

During this period medicine was practiced in barber shops and physicians were indoctrinated by an apprentice system. Sabuncuoglu worked as a surgeon in Amasya Hospital (fig. 2), in what is today northern Turkey, which functioned as a medical school and a surgery residency center. During the Ottoman Empirein the 15th century hospital surgeons occupied an extremely prominent position in society and only the best physicians were eligible. We investigated urogenital surgery in the 15th century, as covered in Cerrahiyyetu’l Haniyye.

Submitted for publication November 11, 2004.

Presented at annual meeting of American Urological Association, San Francisco, California, May 8 –13, 2004.

Health Sciences Center, 1430 Tulane Ave., SL-42, New Orleans, Louisiana 70112 (telephone: 504-988-1631;FAX: 504-988-5059;e-mail: mkendirc@tulane.edu)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A surgical pioneer, Sabuncuoğlu published 3 medical text-books, namely Akrabadin (Pharmacology), Mucerrebname (The Book of Experiences) and Cerrahiyyetu’l Haniyye,1 of which thereare3 known copies, including 1 in Paris2 and 2 in Istanbul.3, 4 The text was written in Ottoman, the Turkish language of the time, with an alphabet that is Arabic in origin. The book also reflects the talents of Sabuncuoglu in painting and calligraphy.

The textbook consists of 190 chapters, which define diseases and surgical approaches, 136 drawings depicting specific operations, 164 drawings of surgical instruments and illustrations of 14 types of incisions. All surgical areas are covered in this book, including neurosurgery,5 and thoracic,6 orthopedic, general,7 pediatric,8 gynecologic,9 plastic,10 vascular and urological surgeries. The book, which reviews basic concepts using original contributions on disease definitions, surgical procedures, postoperative care and surgical instruments, not only guided medical students and surgery residents of the early Ottoman period, but also gives us insight into the surgical operations of that time.12 Cerrahiyyetu’l Haniyye was evaluated with regard to its urological content, including procedures, approaches, and definitions of certain disorders and surgical tools.

FIG.1. Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu (1385 to 1470). Reprinted with permission.

RESULTS

RESULTS

Varicocelectomy. Sabuncuoglu described varicocele or devali as the “bending of testicular veins like a bunch of 1879 grapes.” The cause of this disease, he said, was “filthy blood,” which is not unlike one of the current definitions of varicocele, that is “the reflux of toxic adrenal metabolites.” He used an upper scrotal incision in his varicocelectomy approach. After incising the skin and locating the veins he separated the veins from the vas deferens and then isolated them longitudinally with a wide scalpel or sharp razor where they were dense. With a large needle and curved silk thread he ligated the veins completely from the lower and upper parts.

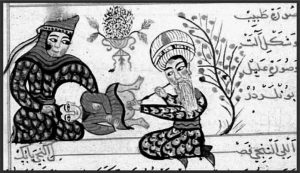

He then dissected the veins between the 2 ligation sutures. He ended the procedure by medicating and dressing the wound. Hydrocelectomy (fig. 3). Sabuncuoglu defined hydrocele as a “fluid collection between the white fascia beneath the skin (tunica vaginalis parietalis) and the fascia surrounding the testis (tunica vaginalis visseralis), resembling a natural capsule.” The color of the fluid was reported to be yellow to crimson to festered darkness but it was white in most cases. “When the fluid is collected between the two tunical layers, it surrounds the testis completely and the sensitivity of the testis is prevented.”

Sabuncuoglu describes an excisional technique for hydrocelerepair. “While the assistant pulls the patient’s penis toward the pubis, the surgeon incises the scrotum longitudinally. After passing all layers, the tunica vaginalis parietalis is opened and the fluid is evacuated. The separated tunica is pulled upwards and the whole tunica is cut away. If it is not possible to excise the excessive tunica from the same point, it is excised part by part.”

FIG. 2. Amasya Hospital was founded in 1308. It functioned as medical school and hospital until beginning of 19th century, when it became psychiatry clinic. Sabuncuoglu served in Amasya Hospital for 14 years as surgeon and teacher. Reprinted with permission.

FIG. 3. Miniature shows hydrocele surgery. Reprinted with permission.13

He cautions that if the sac were not excised appropriately, hydrocele might recur. Sabuncuoglu listed such complications of hydrocelectomy as bleeding, infection and testicular damage done during cauterization. Heasserted that to control bleeding was of principal importance. He writes, “O student, knowest thou that! Ligate all opened vessels carefully. If there is still a chance of bleeding, wheat resin is placed on the opening of the bleeding vessel and cauterization is applied with a sinnare. Thus, the resin covers the opening of the vessel by melting and blood does not flow.” A sinnare is a hook-shaped cautery (fig. 4).

FIG. 4. Sinnare or hook-shaped cautery developed by Sabuncuoglu to control bleeding. Reprinted with permission.13

Urethral surgery. Sabuncuoglu defined imperforated urinary meatus, meatal stenosis and hypospadias as congenital deformities in boys. If the urinary meatus was imperforated, he performed meatotomy using a fine scalpel (fig. 5). After a hole was made he put a slender tin catheter through and tied it. After 3 to 4 days he removed the catheter and observed urination. If the urine stream was not sufficient, he replaced the catheter. Because the catheter provided for urination, it could stay in place until the patient recovered.

Urethral surgery. Sabuncuoglu defined imperforated urinary meatus, meatal stenosis and hypospadias as congenital deformities in boys. If the urinary meatus was imperforated, he performed meatotomy using a fine scalpel (fig. 5). After a hole was made he put a slender tin catheter through and tied it. After 3 to 4 days he removed the catheter and observed urination. If the urine stream was not sufficient, he replaced the catheter. Because the catheter provided for urination, it could stay in place until the patient recovered.

FIG. 5. Dilation of meatal stenosis with dilator. Reprinted with permission.13

He also defined hypospadias. “When the urethral opening is on the ventral side of the penis and if the patients cannot urinate without lifting the penis or if his semen does not flow normally into the vagina, this is also an awful disorder.” In such cases he performed a certain procedure. “The glans of the penis is firmly pulled upwards with the left hand. The glans and urethra are incised at the end of the urethral meatus with a wide knife or scalpel as if sharpening a pencil. It is secured so that the end of urethral meatus settles in its proper place.” After completing the procedure he put a thin catheter through the urethra and sutured the incised sides. Again, he cautioned his pupils about bleeding. “As there would be much bleeding during this surgery, it needs to be done very carefully and the bleeding has to be controlled by a cautery.” Urethrocystoscopy is the gold standard for examining the urethra and bladder. Sabuncuoglu used a rigid 35 cm urethrocystoscope made of silver to observe the urethra and bladder. Using candlelight or sunlight reflected in mirrors he performed endoscopy for diagnosing urethral stricture or bladder stones.

Penile and scrotal lesions. Sabuncuoglu determined whether penile and scrotal lesions were benign or malignant based on their characteristics. After cauterizing these lesions circumferentially with a sinnare he excised them completely. For dressing he recommended a piece of cotton medicated with corn ointment. If the color was off, the lesions were malignant. To treat he first incised and scraped the lesions and then cauterized. If the lesions were on the scrotum, he incised and removed the blackened parts and applied the pounded skin of a pomegranate and vetch flour mixed with honey. He recommended that the wound should be dressed 12 times with the remaining salve. If bleeding occurred during the procedure, he cauterized with a sinnare.

Hermaphroditism. Sabuncuoglu defines 3 types of hermaphroditism. Two of these types are seen in men and 1 is seen in women. One of the male types has something like the sexual organ of a woman between his penis and testicles. The other type has a similar configuration but urine is excreted from there. The similar thing in women is generally on the pubis and it consists of 3 parts, of which 1 is like a penis and the others are like testicles (fig. 6). One of the 2 types is seen in men, from which urine comes out. There is no cure for this. In contrast, the other male and female types may be treated by first excising them in an operation and then dressing the wound until it heals.

Circumcision. Thehistory of circumcision goes back to ancient times. There are different historical perspectives regarding the reasons for circumcision, including religious and hygienic purposes, the acquisition of social prestige, preparation for sexual life, or lessening or enhancing the sexual impulse.

FIG. 6. Surgical approach in female hermaphrodite by female surgeon. Reprinted with permission.

Several methods for circumcision are described in Cerrahiyyetu’l Haniyyein the chapter, “The circumcision of boys and the mistakes made in this practice.” Sabuncuoglu would initiate the procedure by saying pleasant words to the boy and hiding the tools so that they could not be seen. The procedure was performed by cutting the prepuce with a razor, scissors or fingernail. He preferred a straight clamp and scissors of his own design (figs. 7 and 8). After separating the prepuce from the glans penis the prepuce was pulled evenly from each side and fitted with a straight clamp. The prepuce was then cut with curved scissors, and the skin and mucosa were sutured to prevent scarring. He dressed the wound with a wet towel, powder of a dried pumpkin and mill dust until the following day. Yolk oil mashed with rose oil and euphrasy were placed on the wound for 7 days.

The treatment of phimosis and penile warts was also described in detail. “If the prepicium is adhered to the penis, this is called gulfe(phimosis). The causeof this is festering and it is mostly seen in men who are not circumcised. To treat, the end of the adhered part is skinned off with a curved scalpel. The adhered part is separated and the prepicium is freed from the glans. If it is still not separated, a linen cloth wetted with cold water is placed between the prepicium and the glans. By this method, adhesion is prevented. The wound is dressed with Myrtle wine.”

DISCUSSION

Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu is one of the most important surgeons in the history of surgical medicine. He practiced disciplines such as neurosurgery, orthopedics and gynecology, and thoracic, general, pediatric, plastic, vascular and urological surgery. His textbook, Cerrahiyyetu’l Haniyye, which covers basic concepts and includes original contributions on definitions of diseases, surgical procedures, postoperative care and instruments, illustrates the extent of surgical knowledge in the early Ottoman era.

FIG. 8. Circumcision procedure. Reprinted with permission

For almost a thousand years, until the late Middle Ages, Arabic schools pushed the limits of medicine and surgery. This changed during the Renaissance as great Arabic writers, such as Avicenna and Albucasis, were translated into Latin and other contemporary languages, and Western schools became dominant. Because Arabic was considered the scientific language of the era, Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu, who wrotein Ottoman, was for a long time ignored. In fact, it was not until 1939 that the first articleon Cerrahiyyetu’l Haniyye, by Suheyl Unver, was published.14 Finally, after 1960, when Huard and Grmek provided “Le premier manu script chirurgical Turc,”15 Sabuncuoglu started to gain long deserved acknowledgment.

When the horrid hygienic conditions of the 15th century are considered, the surgical procedures of Sabuncuoglu are comparableto those of today. Some, such as those for varicocelectomy and hydrocelectomy, are almost identical. Although he did not citethepossibility that varicocelemay cause male infertility, he reported that the disorder affects the testes. In varicocele surgery he isolated the varicose veins with an upper scrotal incision, ligated the veins with a silk suture and dissected, which is a procedure virtually indistinguishable from the current conventional Ivanisevich technique, which uses an inguinal approach. Because he had knowledge of the content of the scrotum and thetunical layers covering the testes, he preferred an excisional procedurefor hydrocelerepair, which is also in vogue today. He excised the excessive tissue of the tunica vaginalis to avoid recurrence and cautioned his pupils on possible complications.

Sabuncuoglu used a number of surgical tools of his own design, such as scissors, clamps, catheters and drains, in procedures similar to those used by physicians today. To treat hypospadias, which is one of the most intractableab normalities of the urethra, modern pediatric urologists have documented positive results with tubularized incised plate urethroplasty. Sabuncuoglu applied a similar procedure in hypospadias surgery. He used a thin catheter, which provided a proper urine stream until healing. He also developed and used various dilators for the treatment of meatal stenosis and urethral strictures. To observe the urethra (urethral stenosis) and bladder (bladder stones) he performed endoscopy using a urethrocystoscope, which was illuminated by sunlight or candlelight. He also designed and used various cauteries, including round, sharp, olive-shaped, nail-shaped, triangular and crescent-shaped ones, to control bleeding, exciselesions and manage pain. Also, sinceSabuncuoglu operated on the human body well before the concepts of modern sterility and anesthetic management were available, he used combination of mandrake root and almond oil for general anesthesia and analgesia.

Sabuncuoglu was a serious minded and humble researcher, and a superb teacher and clinician. He obeyed the rules of deontology and cared for his pupils during medical training. He explained the complications of his procedures to his patients and obtained informed consent before surgeries. Furthermore, he openly discussed the positive and negative aspects of his techniques, and cited others, namely, Hippocrates, Galen and Albucasis, from whom he gained medical knowledge. From his miniatures we recognize that Sabuncuoglu trained many female and male surgeons.

CONCLUSIONS

Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu is one of the most eminent surgeons in history. His illustrated surgery textbook, Cerrahiyyetu’l Haniyye, written 536 years ago, covered various surgical disciplines, including urology. Basic concepts of urological surgery are discussed in the text, including definitions of urological diseases, surgical approaches, surgical instruments, postoperative care and complications. In light of this seminal work Sabuncuog˘lu must be recognized as one of the great pioneers of modern urology.

Dr. Talip Mert translated the text from Ottoman to modern Turkish and Jason Sparapani assisted with the manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Uzel, I.: Cerrahiyyetu’l Haniyye. Ankara, Turkey: Turkish History Association, 1992

2. Sabuncuoglu, S.: Cerrahiyyetu’l Haniyye. No. 693, 15th century, Turkish suppl. Located at Bibliothe`queNational, Paris,France

3. Sabuncuoglu, S.: Cerrahiyyetu’l Haniyye. No. 79, 15th century. Located at Fatih Millet Library, Ali Emiri Section, Istanbul,Turkey

4. Sabuncuoglu, S.: Cerrahiyyetu’l Haniyye. No. 35, 15th century. Located at Institute of History of Medicine, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey

5. Elmaci, I.: Color illustrations and neurosurgical techniques of Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu in the 15th century. Neurosurgery,47: 951, 2000

6. Batirel, H. F. and Yuksel, M.: Thoracic surgery techniques of Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu in the fifteenth century. Ann ThoracSurg, 63: 575, 1997

7. Bekraki, A., Gorkey, S. and Aktan, A. O.: Anal surgical techniques in early Ottoman period performed by Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu. World J Surg, 24: 130, 2000

8. Buyukunal, S. N. and Sari, N.: Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu, the author of the earliest pediatric surgical atlas: CerrahiyeI Ilhaniye. J Pediatr Surg, 26: 1148, 1991

9. Kafali, H., Aksoy, S., Atmaca, F. and San, I.: Colored illustrations of obstetric manipulations and instrumentation techniques of a Turkish surgeon Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu in the 15th century. Eur J Gynaecol Reprod Biol, 105: 197, 2002

10. Dogan, T., Bayramicli, M. and Numanoglu, A.: Plastic surgical techniques in the fifteenth century by Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu. Plast Reconst Surg, 99: 1775, 1997

11. Darcin, O. T. and Andac, M. H.: Surgery on varicose veins in the early Ottoman period performed by Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu.Ann Vasc Surg, 17: 468, 2003

12. Keskil, S. and Sabuncuoglu, H.: Endoscopy in the 15th century. Minim InvasiveNeurosurg, 45: 45, 2002

13. Kendirci, M., Kadiog˘lu, A. and Mirog˘lu, C.: TheHistory of Male-Female Sexuality and Fertility in Asia Minor (Today’s Turkey). Istanbul, Turkey: Turkish Society of Andrology, pp. 127–147, 2003

14. Unver, S.: Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu: Kitabul Cerrahiye-i Il-haniye. Istanbul, Turkey: Kenan Yayinlari, 1939

15. Huard, P. and Grmek, M.: Le premier manuscript chirurgical Turc Rev Hist Sci, 26: 315, 1973

16. Ganidagli, S., Cengiz, M., Aksoy, S. and Verit, A.: Approach to painful disorders by Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu in the fifteenth century Ottoman period. Anesthesiology, 100: 165, 2004

From the Department of Urology, Health Sciences Center School of Medicine, Tulane University (MK), New Orleans, Louisiana, and Second Urology Department, Sisli Etfal Training and Research Hospital (MK, CM, UB) and Section of Andrology, Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul University (AK), Istanbul, Turkey